12/11: Day 11 🎄

Hot takes and hot chip trays

Welcome back to Unwrapping TPUs ✨!

Finals week final-ly caught up to us, sorry for the delay! Still got a lot ahead to cover, so let’s get into things

. Our last two editions have covered some pretty distinct topics, from how a roofline plot works to our initial research into integrating our TPU RTL modules into an actual FPGA coprocessor.

We’ve spent a lot of our time discussing the logistics of running inference fast, but today we bring our attention back to the TPU v1 paper to continue our coverage and break down one of our favorite parts of the entire publication: the Discussion section.

A bit spicy and a bit punchy, and nothing short of iconic for this legendary paper. These are our notes from the fallacy and pitfall debunking that the authors (and H&P Computer Architecture) expounded upon, and extra tidbits that we found interesting to explore further.

Without further ado…

Debunked: “NN inference applications in datacenters value throughput as much as response time”

In the inference game, there are two key currencies to discuss: throughput and latency. These are not equivalent units, rather two axis to view the compute efficiency map. A common misconception is that you have to pick one over the other. Oftentimes, the throughput becomes more marketable. Afterall, the more TFLOPS or PFLOPS or what have you, the more “powerful” your chip seems.

However, especially in the inference business, low latency remains king. If you process larger and larger batches of data, you can achieve higher efficiency. However, in a real data center serving user applications, especially for the original purpose of Google transcription / translation, inference meant getting results to users fast. If you miss the latency deadline, throughput remains useless.

Debunked: “The K80 GPU architecture is a good match to NN inference” + “The K80 GPU results would be much better if Boost mode were enabled”

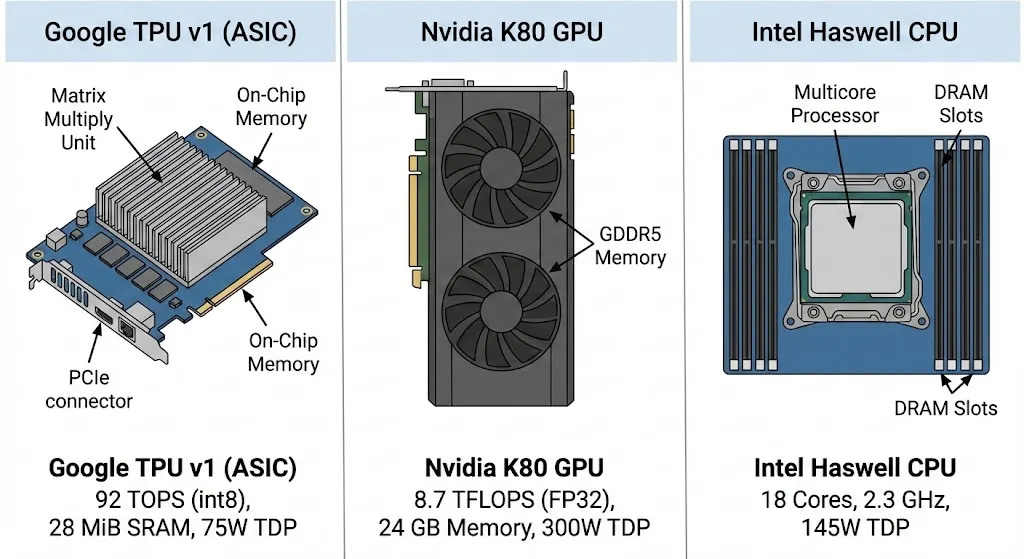

A hot take to call out GPUs, especially today! However, again, GPUs in the 2013-2014 era were still focused on training and running gaming / early crypto workloads. Although AlexNet was just around the corner, the K80 was not built for pure play inference due to strict latency limits, forcing the chip to run with smaller batch sizes. As a result, its massive compute cores were often underutilized as seen in the benchmarking rooflines between Haswell, K80, and TPU v1.

The alluded to boost mode was NVIDIA’s internal overclocking ability on its K80 lineup. However, increasing clock speed (as Dennard scaling’s death had shown) was something of diminishing returns. Increasing clock speed by approximately 1.6x on the LSTM1 model (we suspect this was Translate ASR model, this is not explicitly confirmed, only our estimates based off of provided model specifications) only increased performance by 1.4x while increasing power draw by 1.3x with critically only a 10% boost in performance / watt. In a datacenter, you have to facilitate cooling / power for worst-case spikes. Boost mode as demonstrated would not be sustainable, forcing you to put less GPUs per rack at the cost of a marginal performance boost.

Debunked: “For NN hardware, Inferences Per Second (IPS) is an inaccurate summary performance metric”

In the early days of DNN accelerator profiling, inferences per second or IPS was a unit that was commonly touted for measuring AI chip performance. Let’s break that down. Inferences per second is essentially the number of forward passes completed per second on a given piece of hardware. Model complexity, on the other hand, is the number of work per inference.

Thus, taking hardware throughput fixed at FLOPs per second, IPS is throughput / complexity or roughly available compute per second / compute required per inference. Given that the MLP1 task and CNN1 task differed in performance by 75x on the same hardware, the ability to cherrypick using this statistic would be quite difficult to pin down.

Debunked: “CPU and GPU results would be comparable to the TPU if we used them more efficiently or compared to newer versions”

(Google Nano Banana)

The TPU v1 was built on fixed point numerics, and at that primarily chugging along INT8 MatMuls at that. Yet, despite not using 8-bit AVX instructions in SIMD fashion on the Haswell CPU or the DDR5 from the K80, performance per watt still dominated in both regimes (also given that DDR5 was utilized in K80 as compared to DDR3 on TPU v1). In the CPU vs TPU V1 comparison, the TPU maintains a 12-24x performance / watt improvement and 3x the performance / watt using K80’s DDR5.

Debunked: “After two years of software tuning, the only path left to increase TPU performance is hardware upgrades”

Although there were two years of initial tuning since the original 2013 deployment of TPU v1 when published in 2015, software is always of significant performance tuning potential. Complex models are constantly being released, as seen as the advent of the transformer, and hardware-software co-design constantly is in need of adaptation to these technological tides. By reorganizing the batch sizing, fusion, and utilization, even at the 2-year point, the TPU v1 authors pointed to significant further potential tuning.

Pitfall: “Performance counters added as an afterthought for NN hardware”

Performance counters are tiny hardware-tally registers primarily used for cycles, instruction completion count, cache misses, and branch prediction. In the case of the TPU v1, these counters are used to build profiles of the MMU activity, stalls, and data validity. However, the quantity of performance counter to the TPU DSA couldn’t distinguish between idle time root casues. Additionally, non-matrix cycles are a grouping for all unexplained cycles, which subsequent TPU generations resolve.

Throughput vs latency, inference benchmarking units, boost mode, GPU vs CPU vs TPU, model benchmarking, software ceiling, performance counters galore! So many interesting asides to consider…

Works Referenced

Jouppi et al. In-Datacenter Performance Analysis of a Tensor Processing Unit